How Indigo Became The Signature Shade At The Heart Of Black Fashion

If the sight of a cotton plant stirs up layered, confusing feelings within you, you are not alone. This titan of a crop is woven into countless household items, has […] The post How Indigo Became The Signature Shade At The Heart Of Black Fashion appeared first on Essence.

If the sight of a cotton plant stirs up layered, confusing feelings within you, you are not alone. This titan of a crop is woven into countless household items, has generated wealth beyond comprehension, and also has a haunted history of exploitation and violence.

At one period in time, cotton and indigo were the most powerful forms of currency in the developing world and served as necessary keys to the Industrial Revolution. To understand the impact of cotton, indigo, and, by extension, denim, on the evolution of fashion at large, one must understand the origins of the textile industry and slave labor itself.

In a general sense, many of us knew how instrumental cotton was to the business of chattel slavery. It’s worth noting we also know how instrumental chattel slavery was to the foundation of the American economy, and thus the world economy. When Black folks say, “There wouldn’t be anything without us,” this is not hyperbole or a general statement that could apply to our many undeniable influences across the world. It is a fact. No large structure, economy, or industry as we know it today would exist without the contributions enslaved Africans made to the cotton industry.

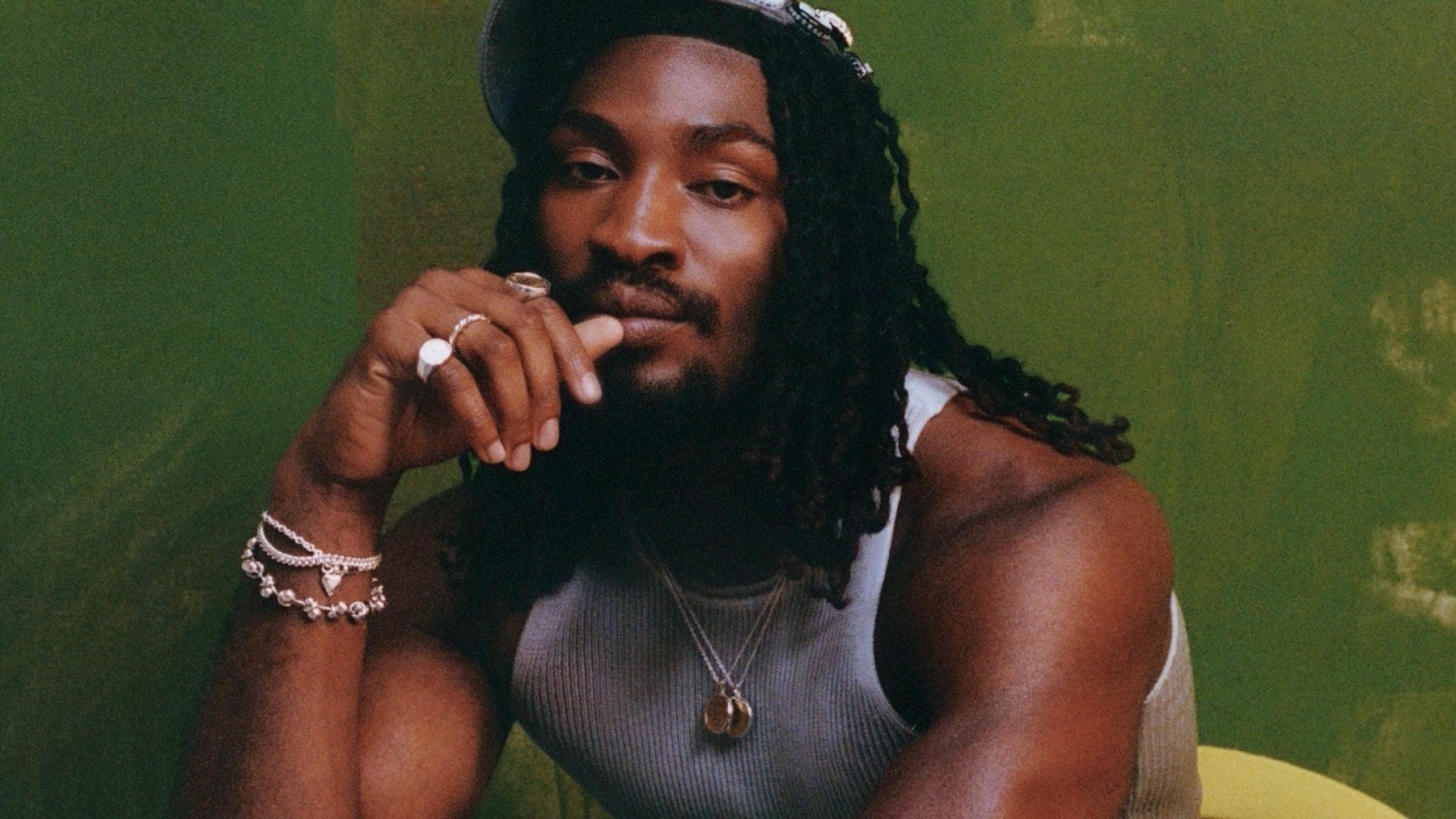

Courtesy of Oak & Acorn

Courtesy of Oak & Acorn It is no wonder, then, why Black people, and Black Americans specifically, have such a strained relationship to the raw material of cotton, and at the same time, such an unconscious connection to denim. A few years ago, I had the pleasure of meeting global designer and celebrity stylist-turned-sustainable designer Miko Underwood at the Black In Fashion Council’s Discovery showroom. While looking at pieces from her brand, Oak & Acorn, I expressed my fondness for and natural gravitation to denim. She suggested it was innate, ancestral even. Another recent conversation with Underwood led to key conversations with figures who encompass the global fashion industry, the materials market, and the global economy.

The Global TrailOver a video call, Miko, who originally launched Oak & Acorn in 2019, broke down exactly how the original development of indigo was born from a global conversation. The indigo plant is a genus encompassing several species, native to regions including India, West Africa, and the U.S. The most manufactured species for European trade were cultivated by enslaved Africans for American and Caribbean soil, using the agricultural knowledge they brought with them from their homelands. Enslaved peoples in the South and Caribbean, such as Louisiana, South Carolina, and Georgia, but also Haiti, Jamaica, and Barbados, regions that saw a significant amount of overlap and in-trading, developed indigo production for European colonizers.

Courtesy of Miko Underwood

Courtesy of Miko Underwood Dominique Drakeford, sustainable fashion advocate, podcast host, and creative director, best frames the conversation by stating: “Before cotton became king, indigo was the original Blue Gold that quietly bankrolled colonization.” She adds that European enslavers were deliberate in their abduction of certain West African people for their mastery of the plant, its dyeing properties, and their fabric-weaving skills. They harnessed ancestral practices to produce indigo-dyed garments and goods, which were then lauded as a luxury to unfamiliar Europeans, advancing colonial trade power.

By the late 1700s, the novelty of indigo production withered some, and into the 19th century, cotton replaced indigo as the British Empire’s most lucrative crop. Exporting cotton from Southern states such as Mississippi at a massive scale and utilizing it to develop their industrial markets made the U.K.’s economy dependent on the plant. Stephen Satterfield, a sommelier and food anthropologist specializing in the origin, foraging, and reclamation of cotton, specifies how cotton production, produced off the backs of Black slaves in the American South, was the foundation upon which capitalism was born. Satterfield explains that the British, exporting little to no goods of their own, focused on industrialization, utilizing cotton and its laborers as both product and currency.

“You [couldn’t] grow cotton in England, and yet, they made the decision to base their entire economy on manufacturing something that didn’t grow in their own backyard,” Satterfield added. He expresses that cotton, and by extension, slavery, became the preeminent institution that was far more lucrative than the raw material itself. “It was the economy that was built around raw material.”

Courtesy of Tameka Peoples

Courtesy of Tameka Peoples Similar to how gold backs the dollar, cotton backed slave labor. To emphasize, cotton was the product fueling this new industry, and enslaved people were the collateral used in place of bank loans, insurance, and literal currency. The manufacturing and banking systems that came from this industry developed into the capitalist economy we experience today.

Tameka Peoples, founder and CEO of sustainable cotton manufacturer Seed2Shirt, deepens this perspective by pointing to the sheer economic gain at hand. Citing a US Census Bureau of Labor and Statistics’ report on cotton production, Peoples reveals that they recorded “18M pounds of cotton production from 1784 to 1920.” According to the Federal Reserve Bulletin, for the year 1800, $5 million of exported cotton value alone was generated from the American cotton industry, not accounting for inflation, which increased roughly 10% per year. Considering compounding inflation, we can understand that the revenue generated from enslaved people’s cotton production backed the earlier British and American economies.

Indigenous Creativity and Sustainability Paved the Way For Global InnovationDrakeford asserts that long before synthetic dyes and imported sarongs hit curated racks, Black hands “were cultivating indigo as a part of a regenerative, spiritually-rooted relationship with the Earth.”

Global Indigenous communities from Africa to Turtle Island have perfected fabric weaving, dyeing, and craftsmanship over thousands of years. Without such advanced textile fabrication, the textile and garment industry would not be what it is today. Europeans depended on Indigenous ingenuity and sustainability practices to create the products that fueled their economies.

The practices of using Earth-derived materials held both physical and spiritual applications. Indigenous communities such as the Pueblo and Navajo were manipulating cotton fibers long before colonizers laid claim to their lands. As Drakeford notes, West African communities across pre-colonial Ghana, Cameroon, and beyond were dyeing fabrics and weaving plant fibers into patterned cloths and applied that knowledge to new lands. Afro-Indigenous practices survived with them through slavery and genocides, alchemizing into preserved creations such as quilting and pattern-making.

Courtesy of Dominique Drakeford

Courtesy of Dominique Drakeford When thinking further of Indigenous contributions to the industry, Satterfield puts forth a harrowing reality: atrocities such as the Trail of Tears and other mass eradications were done for the purpose of expanding the textile industry. Peoples offers the example of Pima cotton, which is still one of the most premium strains of cotton today. Named after the Pima tribe originating from the western region of the Americas, this strain of cotton was cultivated from a series of selective breeding, learned from the Pima people, and adopted by enslaved Africans in the South. Black people’s direct contributions of physical and mental labor streamlined cotton manufacturing, outlining work processes and exploitation, which are evident across the fashion industry today. Drakeford impresses the importance of noticing these connections from innovative design creations to the brutality of sweatshops. “Plantation capitalism [was] the original fast fashion model,” Drakeford said.

Fashioning ResistanceIn Underwood’s own words, “Denim became the language of liberation.” She goes on to detail the countless ways the fabric has shown up across American culture. Before denim was a stylish material worn by coastal communities, cowboys, and began taking up space in Southern culture, it was the original material used for the “Negro Cloth,” and reclaimed across generations as a symbol of creative resilience. The negro cloth was often coarse, durable fabric given to slaves to makeshift clothing out of. Through their knowledge of indigo dying and upcycling, they created for themselves the first iterations of denim.

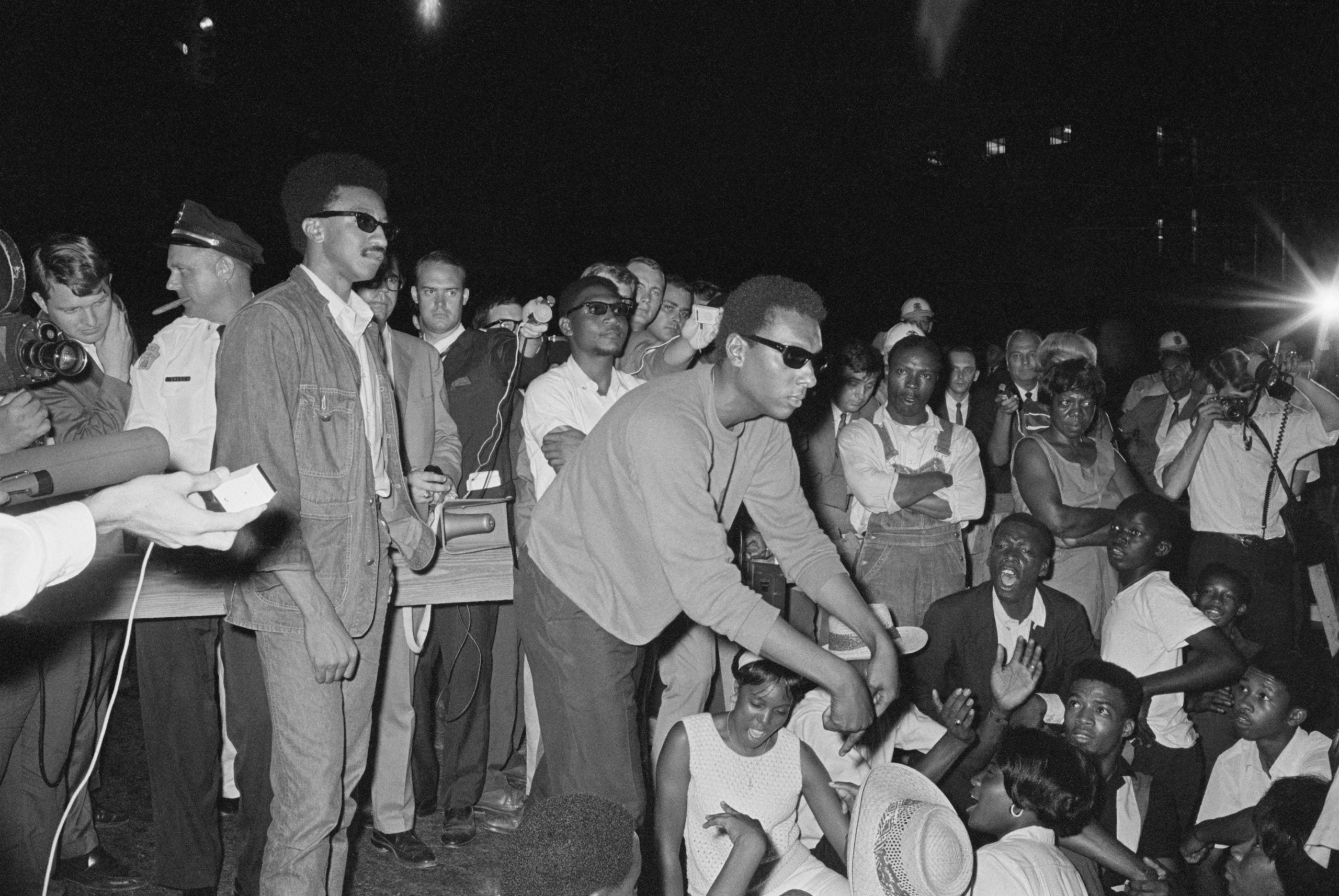

Due to its connotation with slavery and Black Americans, denim and indigo were not always celebrated, especially by Black Americans seeking forward mobility and civil rights. It was often relegated as workwear for its durable, casual material. Drakeford and Underwood explain that it was not heavily reclaimed until the young activists of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) began wearing denim jeans as both protest and protection.

Denim served as physical protection against the chemicals, food, and other material being thrown at them during protests, and defied the respectability politics that tried to convince them that their worth was conditional to their presentation. The material soon became the uniform of resistance for many American social movements including the Gay Rights Movement and the Workers’ Movement.

Getty Images

Getty Images Drakeford points to the connection of fabric dyeing across the diaspora. Formerly enslaved Caribbeans used bold colors as a means of resistance, which paved the way for the vibrant attire synonymous with Carnival. Their use of bold colorways can also be seen across global Caribbean communities such as in London and Brooklyn.

Further, sustainability is foundational to Black creation. Consider: patchwork clothing across the Caribbean and quilting traditions of Gee’s Bend in the American South, merged as communities migrated and converged. This culminates in later examples such as Dapper Dan’s influence in Harlem, which led to hip hop culture popularizing logomania and oversized denim. Upcycling has been a part of our culture from the very first strip of negro cloth.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images From the use of indigo and blue for spiritual protection by Mississippians, as depicted in Ryan Coogler’s “Sinners,” to the denim blue incorporated into Beyoncé’s “Cowboy Carter” era wardrobe and storytelling, indigo and cotton are staples of Black resistance and creativity. Spanning beyond physical protection and reclamation, indigo’s spiritual significance stems from pre-colonial Africa to the foundational heritage of Black people in the American South, as expounded by Imani Perry in her book, Black in Blues: How A Color Tells The Story of My People (2025).

Reclaiming MaterialHolding the weight of cotton’s influence on the world, and thus the instrumentality of Black labor, is painful, yet necessary work. Cultural stewards such as Peoples, Satterfield, Underwood, and Drakeford sustain this work to reclaim cotton and indigo for Black diasporic people. Slavery, sharecropping, and systematic disenfranchisement of Black farmers has left a stain on cotton production in the eyes of Black Americans and erased the vital links between indigo and our ancestral practices.

Courtesy of Stephen Satterfield

Courtesy of Stephen Satterfield Satterfield works to address this generational wound through his cotton manufacturing and apparel company Comoco Cotton. The textile manufacturer reclaims the growth of cotton for Black farmers, compensating 20-50% higher than the minimum rate and building a DTC model that cultivates a healthier relationship with apparel and creation.

People’s company Seed2Shirt prioritizes sustainable, regenerative cultivation practices at every step of the product’s life cycle. Utilizing a vertically integrated manufacturing model, it works to center Black cotton farmers across the U.S. and Africa to ensure the artisans whose hands create the product also benefit from said product.

Underwood’s clothing brand Oak & Acorn prides itself on creating heritage denim. It continues the Black American tradition of indigo-dyeing, natural fabric weaving, and deadstock upcycling to create a fashion brand rooted in culturally-conscious work. Through her podcast, “Compost, Cotton & Cornrows” and her role as creative director of the documentary series, “The Black Farmers Project,” Drakeford works to help Black diasporic people make connections between themselves and the origins of sustainability, agriculture, and fashion. She has also dabbled in the Black farm-to-T-shirt ecosystem through a collaboration with Peoples, importantly noting that Peoples is a pioneer in the space.

The connections African diasporic people have to cotton, indigo, and denim are ancestral, spiritual, revolutionary, and painful. They are also still living. Cultural stewards such as the aforementioned preserve this living, breathing legacy through a healing reclamation of craftsmanship and history. In doing so, they affirm the impact of Black ingenuity throughout time, resisting history’s attempt to minimize or erase our necessity to human evolution. By highlighting the connections of these subjects to Black innovation and labor, Drakeford, alongside her expert peers, encourages Black diasporic people to find pride and power in the material goods that sustain the global economy.

TOPICS: black history fashion history indigoThe post How Indigo Became The Signature Shade At The Heart Of Black Fashion appeared first on Essence.