Juvenile Detention Centers: No School, No Fresh Air and Isolated

This story was originally published by MLK50: Justice Through Journalism. Subscribe to their newsletter here. In the hours after 17-year-old David was locked in housing unit H, voices filtered into his cell. The sound came from multiple places at once: the seams of the door, the vent by the ceiling, the walls themselves. They knew he’d just […] The post Juvenile Detention Centers: No School, No Fresh Air and Isolated appeared first on Capital B News.

This story was originally published by MLK50: Justice Through Journalism. Subscribe to their newsletter here.

In the hours after 17-year-old David was locked in housing unit H, voices filtered into his cell.

The sound came from multiple places at once: the seams of the door, the vent by the ceiling, the walls themselves. They knew he’d just arrived, and now they wanted to know who he was. Why was he there?

The children in the surrounding cells were trying to speak to him, he realized. Just as they were curious about him, he had a question for them. Where was he?

“You’re not going to be coming out any time soon,” he remembers them saying. “You should just try to lay down.” He was in a place they called “the hole” — a solitary confinement unit.

David was incarcerated in Shelby County’s juvenile detention center, the Youth Justice and Education Center, in 2024. He was kept there for eight months. The name David is a pseudonym of his choosing; he has been granted anonymity to protect him from potential retaliation.

Juvenile detention centers, similar to jails in the adult system, house youth who have been charged with a crime but who have not yet been found innocent or guilty. They are not being punished; instead, they are waiting for their court cases to be resolved. In other words, when David was incarcerated, he did not know when he’d be released.

Around five months into his incarceration, David started a fight. In a moment of frustration — the longer he stayed in detention, the more he lashed out — he punched a kid he already didn’t like. In response, guards moved him from his residential housing unit, E-pod, to housing unit H.

It took nearly two days for guards to let David out of his cell in H-pod. They allowed him to take a shower and briefly call his mother before locking him up again. For the next three months, David was isolated in an area less than half the size of a parking space for up to 71 hours at a time. There was no school, no fresh air and almost no time with other human beings.

“I had nothing to do, nothing to learn, nothing,” he said.

He thought he’d been put in H-pod because he’d been fighting. But spending so much time alone started to make him feel violent. “You’d think they actually want you to fight,” he said. “I couldn’t do anything but do pushups and get mad and think about stuff. It makes you want to come out and put your hands on somebody.”

As of Wednesday Oct. 1, the Shelby County Division of Corrections operates the Youth Justice and Education Center. The Shelby County Sheriff ran the center from 2015 through September 2025.

At one point, David asked a sheriff’s deputy why he couldn’t at least go to school. “If you were on a regular pod, you could go to school,” David remembered the deputy saying. But he wasn’t on a regular pod anymore. “Welcome to solitary confinement,” the deputy told him.

Children incarcerated in Shelby County’s juvenile detention center are frequently held in solitary confinement, according to more than two dozen sources who spoke with MLK50: Justice Through Journalism.

Tennessee law prohibits holding children in seclusion, a term often used interchangeably with solitary confinement, for longer than two continuous hours. But according to source accounts, the center has two solitary confinement units — D-pod and H-pod — where children as young as 13 are confined to their cells for 23 hours or more at a time, for periods of weeks or months. According to records reviewed by MLK50, one of these confinement units, D-pod, has existed since late 2023.

D-pod and H-pod are “behavior — not confinement — units,” a spokesperson for the Shelby County Sheriff’s Office told MLK50 in a written statement. “They have the same activities as other housing units except they are not allowed to be with the others due to their disruptive behavior.” They also said youth had not been placed in D-pod or H-pod as punishment.

The sheriff’s office denied that youth in the center have been kept in solitary confinement. Still, a spokesperson for the sheriff declined to share how they define the term.

As of 2021, Tennessee law defines seclusion as the “involuntary segregation of a child from the rest of the resident population,” even when children can see or hear other youth in their housing unit. But the Tennessee Department of Children’s Services, which licenses the Youth Justice and Education Center, has a different definition of seclusion in its rules for Juvenile Detention Centers. DCS’s rules, which were last updated in 2017, state that seclusion does not include “confinement to a locked unit or ward where other youth are present.”

In this article, MLK50 is using the United Nations’ definition of solitary confinement — “the confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact.” The United Nations also describes “prolonged solitary confinement” — periods of solitary confinement that last longer than 15 days — as a form of torture.

Records show that Memphis-Shelby County’s Juvenile Court has been aware that youth in D-pod are separated from the general population and confined to their cells for most of the day since at least 2024. During the same time period, juvenile court magistrates incarcerated more youth at the center than the previous court administration, even as the number of youth charged with serious offenses declined. Despite multiple requests for comment, a court representative did not provide a statement for this article.

Meanwhile, inspection records show Tennessee’s Department of Children’s Services has been aware that youth in D-pod are separated from the general population since at least 2024. DCS was also aware that youth in D-pod are not allowed to attend school. A DCS spokesperson said they were not aware of any use of solitary confinement inside the center.

One parent told MLK50 that his son became suicidal after several weeks in D-pod. In 2024, the Shelby County sheriff recorded 50 suicide crisis calls — a 16% increase over the previous year — and 14 suicide attempts among children incarcerated at the detention center, after reporting none the year before.

“It’s a pressure zone”

There were no clocks in H-pod, David realized.

He kept track of time through his meals. When it was time to eat, deputies opened the door to his cell, handed him a tray and then closed the door again. If he was being served breakfast it must be 7 a.m., he thought, reasoning from his experience in E-pod. If they gave him lunch, it must be noon.

If nothing else, there was a clear distinction between day and night. Each cell had a fluorescent overhead lamp that emitted a piercing white light during waking hours. The lights never went out, he said. Instead, guards marked each evening by flipping a switch that turned the pod a muted orange.

Most youth didn’t sleep at night, David said. Instead they’d scream and yell, using the vents, the cracks and the strength of their voices to communicate with each other. “They’d be up all night, arguing,” he said. “You wouldn’t be able to sleep until 3 or 4 a.m.” The next day, they’d nap well into the afternoon.

They stayed up at night because they had little to do during the day, he added.

They were confined to cells a little larger than a king-sized mattress, with a concrete shelf that served as a bed, a thin mat laid over that concrete, an itchy blanket and no pillow. In the corner, there was a metal toilet and sink. There were two narrow windows on either side of each cell; one embedded in the cell door, and one that offered a view outside. Beyond this, there was nothing.

Looking back, it is difficult for David to recall exactly how he spent most of his time in that cell. How does one describe a period characterized by absence?

It is simpler to catalog what he lacked. In E-pod, there were books to read inside his cell; in H-pod, there were none. There were no games to play, no time outside. He would sometimes speak to another child through the walls — usually, they’d talk about what they’d do when they were free — but their conversations always petered off. “There’s only so much you can talk about,” he said.

He took to staring out of his window. He could see a sliver of the gravel road outside the detention center, and monitored it for hours at a time. He’d track the movements of other people: the sheriff’s deputies who came in and out each day, youth who had been arrested, youth who had been discharged. When he recognized one of the kids leaving, he’d tap on the glass of the window, wave and try not to wonder when he’d take their place.

At points, he became restless. He’d run in place for as long as he could, do pushups and a few jumping jacks each day. Sometimes he’d jump off his bed, land on the floor and jump back again.

“If you don’t move around, it’ll take a toll on you,” he said.

The other kids were restless, too. They were angry that the guards wouldn’t let them out, and found ways to retaliate. “They’d poop on their clothes,” he said. “They’d bust the sprinklers, or bust the toilet.” The entire pod constantly smelled of sewage.

Solitary confinement seemed to dissolve one’s inhibitions, David noticed. “It’s a pressure zone,” he said. “Those who can pop, do it.”

When he was briefly let out of his cell — usually, every other day but sometimes every three days — he could make a phone call, which he thought was supposed to last a half hour. He suspected these calls were sometimes cut short by guards; they’d tell him 30 minutes had elapsed, even as he felt it might have been five or 10 minutes less than that. After being incarcerated for several months, “you know what a 30-minute phone call is,” he said. Still, he had no way to prove they had lied.

It was all messing with his head. His thoughts raced, and he felt surges of anger he couldn’t explain.

“I didn’t think I was ever coming home,” he said. He often wished he could just see his mother. Before his incarceration, “I was used to seeing my mama every day,” he said. In H-pod, he saw her in person for a half hour once each week, if that.

Eventually, he stopped himself from thinking about home at all; those kinds of thoughts would “mess you up,” he said. Instead, he thought about what the next few years might be like if he stayed in jail. He decided he didn’t care. As long as he wasn’t in H-pod anymore, he could tolerate it.

Solitary confinement’s impact on adolescents

Solitary confinement units are not uncommon in American prisons and jails, said Dr. Terry Kupers, a psychiatrist and professor emeritus at the Wright Institute who has served as an expert witness in dozens of lawsuits about conditions in correctional facilities. Kupers is also the co-author of “Ending Isolation,” which argues that the practice of solitary confinement should be abolished.

It wasn’t always this way. When Kupers began practicing five decades ago, solitary confinement was rarely used, he said.

“Back in the ’70s, the problem was overcrowding,” he said. “There were all these laws that made sentences for just about every crime worse. And so the jails and prisons got very crowded. When you crowd jails and prisons, the social science research shows you have an increase in the rate of violence, the rate of mental breakdown, the rate of suicide, et cetera.”

Prison officials began to use solitary confinement to reduce that disorder, Kupers said. “In the 1980s, the prisons were totally out of control,” he said. “All over the country, there were what they called riots. Often it was prisoner hunger strikes and resistance wanting better conditions, but they called it riots. So the state said, ‘We know what we’re going to do about this. We’re going to lock down the prisoners.’ They started building these solitary confinement units, entire cell blocks or prisons dedicated to solitary confinement.”

That trend spread to juvenile facilities, said Mark Soler, the former executive director of the Center for Children’s Law & Policy.

“What happens is the staff put the young people who they consider to be the troublemakers in the lockdown unit,” Soler said. “They don’t have anything to do. That’s a critical characteristic of this situation: The kids don’t have anything to do.”

By his own estimation, Kupers has now interviewed over a thousand people who have spent time in solitary confinement. In the process, he developed a framework for what solitary does to the human mind.

The primary characteristic of solitary confinement is a forced lack of social interaction, Kupers said. It is accompanied by few amenities or constructive programming. “It’s isolation and idleness,” he said.

Our most basic needs are often understood physically: food, water and shelter. But social interactions are “central and critical to being human,” Kupers said. When one is deprived of those interactions, the brain begins to malfunction.

People kept in solitary confinement for long periods of time “have severe anxiety, including panic attacks,” he said. Often, they find it difficult to sleep. “There’s noise in solitary confinement, which keeps you from sleeping. But the anxiety also keeps you from sleeping.”

Eventually, “Their thinking becomes disordered,” he added. “They become paranoid, they become very depressed. Despair is widespread.”

Sometimes, people locked in isolation units may be able to speak with each other. That doesn’t mean it’s not still solitary confinement, said Kupers.

“People talk through the heating vents or scream out in the open air space and someone answers them,” he said. “That’s not meaningful human communication.”

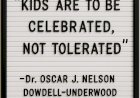

Adolescents have a particularly acute need for other people, Kupers said. “There’s a very narrow window in adolescence when people are accruing social skills, emotional skills, educational capacities,” he said. “If they don’t get it, often they can’t go back and get it later.”

In solitary confinement, one might find that mental tasks that used to come easily are now impossible.

“People have problems with concentration and memory,” Kupers said. “I say to people in solitary, ‘You know, if I was in solitary, I would read everything I could get my hands on.’ And they tell me, ‘Well, I try to do that, but in fact, I can’t remember when I read the page before, so I gave up reading.’”

People held in isolation often start to behave strangely. “They do compulsive things,” he said. “They pace, they count the cinder blocks making up their cells.” Some have psychotic breaks.

“Another symptom is mounting anger,” he added. “Then they’re terrified that [that anger] will get them in trouble with the staff and they’ll have a longer time in solitary. This happens a lot with kids who tell me, ‘I’m never going to get out of here.’”

Solitary confinement is typically intended to control bad behavior, said Kupers. But it’s more likely to make behavioral problems worse.

There are other ways of managing misbehavior, Soler said. “The staff should talk to the youth and ask, ‘What’s wrong, what’s the problem?’” he said. “Kids do things for all kinds of reasons, but they generally have a reason. Staff should be talking to the child to find out what the problem is.”

“Putting kids in solitary is not going to have a deterrent effect. Kids don’t think into the future in terms of the consequences of their behavior,” he added. “You lock kids up in their room, and all they do is think about how angry they are.”

The most severe consequence of solitary confinement is suicide, said Soler.

“I have represented families of children who have killed themselves in jail cells,” he said. “The truth is, if you’ve got a child who’s really in crisis, a child who can’t control themselves, something really bad is going on around the child. The last thing you want to do is leave the child alone, because they’re just going to get more and more depressed, and that’s when they start thinking, ‘I have no future. I have to end my life.’”

Most youth who commit suicide in juvenile facilities are either in solitary confinement or have been held in solitary confinement in the past, according to a 2009 U.S. Department of Justice report.

One father told MLK50 that his son, who had been held in D-pod for weeks, became suicidal last winter while in solitary confinement.

When asked if youth in solitary confinement units ever became suicidal, a sheriff’s office spokesperson reiterated that youth in D- and H-pods were not being held in solitary confinement.

At a different point in their statement, the spokesperson wrote that “Mental health staff work closely with these youth as the goal is to return them to the other housing units.”

Memphis-Shelby County Juvenile Court knew about solitary confinement

Ala’a Alattiyat first heard about the Youth Justice and Education Center’s solitary confinement units about a year ago.

Alattiyat is the coordinator for the Youth Justice Action Council, “a coalition of justice-impacted and connected youth and adults who want to change the way the so-called ‘youth justice’ system works in Memphis,” she said.

Last summer, Alattiyat was tasked with finding youth who might participate in the council; ideally, youth who had experienced Shelby County’s juvenile justice system firsthand. She began to show up at community centers and schools around the city.

She started encountering youth who had been incarcerated in the Youth Justice and Education Center almost immediately. When she asked them what it was like there, they described solitary confinement.

“I recall one young person describing it like how an adult would,” she said. “He said, ‘They put us in the hole.’ I think he said he was in the hole for multiple weeks.”

Eventually, Alattiyat recruited a group of youth for the council. In early 2025, one of those youths was arrested and incarcerated at the juvenile detention center, where he remained for seven months.

At first, Alattiyat heard from him frequently. But as time went on, his communications became sporadic. He’d started fighting, she said, and was moved to H-pod as punishment.

“I was like, ‘So what does that mean?’” Alattiyat remembers. She asked the other youth in the Youth Justice Action Council if they’d heard of H-pod. “That means he’s in solitary,” they told her.

Under a 2021 state law, seclusion is defined as “the involuntary segregation of a child from the rest of the resident population, regardless of the reason for the segregation, including confinement to a locked unit or ward where other children may be seen or heard but are separated from those children,” said Zoe Jamail, a former policy director at Disability Rights Tennessee who co-authored a report alleging abuses at the Wilder Youth Development Center in Somerville, Tennessee.

The law permits seclusion for up to two hours continuously, and no more than six hours in an entire day. It forbids seclusion for any length of time for punishment, administrative convenience or as a response to staffing levels.

Despite this, the Youth Justice and Education Center appears to have two solitary confinement units where youth are held in seclusion for much longer than two hours at a time.

The center opened in July 2023 as a replacement for Shelby County’s previous juvenile detention center. According to Department of Children’s Services inspection records and blueprints reviewed by MLK50, the center has eight residential housing units. Six of these housing units have 12 cells; the remaining two, D-pod and H-pod, have 25 each. According to DCS inspection reports obtained via records request, when the facility opened, these two larger housing units were intended to house youth who had been “bound over,” or transferred to the adult system.

But halfway through 2023, magistrates in Memphis-Shelby County’s Juvenile Court began to incarcerate more youth. Correspondingly, the detention center’s population rose rapidly. In response to this increase in population, the center moved youth who had been transferred to the adult system to an adult facility, Sheriff’s Office Chief Inspector Kimberly Lee told a DCS inspector, who documented their conversation in an inspection report obtained via records request. According to sheriff’s office jail report cards, these youth are now incarcerated in Jail East.

In the absence of those youths, sources say, D-pod and H-pod have been repurposed into solitary confinement units. A spokesperson for the sheriff’s office wrote that these pods are “behavior — not confinement — units.”

“D-pod was designated as such in late 2023 or early 2024,” the spokesperson wrote. “H-pod was designated as such in 2025. These are needed to house disruptive youth who fight with others for the safety of the other youth, staff, teachers, etc.”

Youth are not sent to D or H-pod as punishment, the spokesperson added. Still, “their behavior dictates their placement,” he wrote.

When asked if youth could be held in D-pod or H-pod for periods of weeks or months, the spokesperson told MLK50 that “This would be determined by their behavior.”

In March 2024, Lee informed a DCS inspector that children in D-pod had been separated from the general population, according to a DCS inspection report. This unit was now “a pod for youth that had behavioral issues” including “fighting in school or mental health concerns.” They did not yet have “educational services” inside D-pod, though she said they planned to provide them in the future.

In his report, the inspector noted that he did not speak with children inside D-pod. In later inspection reports, DCS inspectors did not record any follow-up attempts to talk to those youth.

When asked about allegations that youth were held in solitary confinement in D-pod, a Department of Children’s Services spokesperson told MLK50 that inspectors were not aware of any instances of solitary confinement inside the center.

The state’s Board of Education requires four hours of education per day inside juvenile facilities. When asked why DCS had not pursued corrective action once an inspector learned that children in D-pod were not attending school, a spokesperson said that Memphis-Shelby County Schools — not the Department of Children’s Services — is responsible for ensuring that youth inside the center access education.

When asked whether youth in D-pod and H-pod have been barred from attending school, the sheriff’s office spokesperson wrote, “They may be removed from school attendance due to conduct but once they are able to control themselves, they are returned to school.” At the same time, the spokesperson acknowledged that when youth are placed in D-pod or H-pod, they are kept separate from the rest of the detention center’s population.

Leadership in Memphis-Shelby County’s Juvenile Court also seemed to be aware of one of the solitary confinement units. In November 2023, a consultant hired by juvenile court visited the center. His official report, which was issued in July 2024 and obtained via records request, noted that “unit D is being operated as a behavioral confinement unit” and within unit D, “most, if not all youth” had not been let out of their rooms that day.

During a March 2025 meeting to discuss the juvenile detention center transition, the court’s chief judicial officer, Erica Evans, acknowledged that children in the center were being held in solitary confinement, according to a recording one of the meeting’s participants gave MLK50.

“When we’re talking about visitation and 23 and 1, Tennessee rules explicitly discuss that and what the minimum requirements are, and we know they’re not being met right now,” she said. Evans did not respond to a request for comment.

The same source who provided MLK50 with this recording said that “23 and 1” is a common term used to describe solitary confinement inside the center, in which one is confined to a cell for 23 hours a day.

Despite reports of solitary confinement inside the center, juvenile court magistrates continued to incarcerate more youth in the center than the previous court administration.

Children in the Youth Justice and Education Center have not been found guilty of any offense, nor are they being punished. Juvenile court magistrates incarcerate children who have been deemed a flight risk or a threat to the community.

In Shelby County, juvenile court cases can last months. Some youth are incarcerated until their cases are resolved, though magistrates can choose to release them at any time. According to the court’s own data, it is now increasingly common for the court to keep youth in the detention center for 90 days or more.

MLK50 sent juvenile court multiple requests for comment. A juvenile court spokesperson did not provide a statement for this article.

David was incarcerated for eight months, the entirety of his case. He had been charged with two class-B felonies, including aggravated robbery, and court records show prosecutors briefly attempted to try him as an adult.

David says he didn’t commit the robbery, though records show he was adjudicated delinquent, the rough equivalent of being “found guilty” in the juvenile justice system.

Still, David was never tried as an adult, nor was he incarcerated after his case ended. Instead, court records show he was electronically monitored for three months following his release — less than half the time he spent in the detention center.

David spent the last months of his incarceration in housing unit H. The day he finally left the pod was also the day he went home, in early 2025.

It feels good to be free, he said. “Now I can do what I want to.”

Still, incarceration has left its mark. To this day, he can’t deviate from the mealtimes set by detention center staff. Every time he drinks a glass of water, he remembers the feeling of his throat drying out as he waited hours for guards to bring him a cup. Each time he sees a school resource officer at his high school, he has to remind himself not to be afraid. And when he goes to sleep, his dreams tend to take him back to his cell in H-pod.

“It’s like you’re free, but your mind is still locked up,” he said.

Rebecca Cadenhead is the youth life and justice reporter for MLK50: Justice Through Journalism. She is also a corps member with Report for America, a national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms. Email her rebecca.cadenhead@mlk50.com.

The post Juvenile Detention Centers: No School, No Fresh Air and Isolated appeared first on Capital B News.