Democracy Shouldn’t Be a Luxury Item But That’s What It’s Become

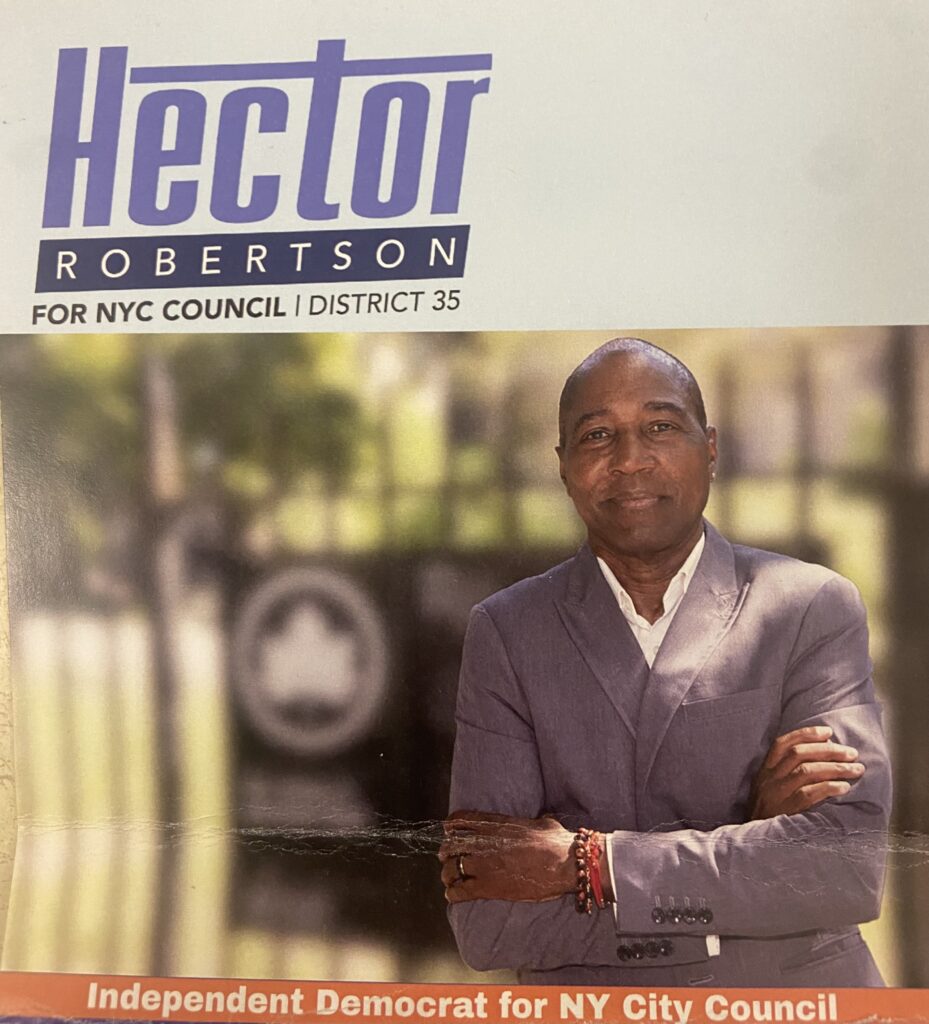

By Hector Robertson, Candidate for City Council, District 35 (Brooklyn) I’m running for New York City Council in District 35, not because I come from money, and not because I have deep-pocketed donors or political endorsements. I’m running because I’ve experienced the struggles that too many in our community face: skyrocketing rents, under-resourced schools, and a political system that too often leaves us out. But from the moment I launched my campaign, I ran into roadblocks, not just from the usual challenges of organizing, but from the very system that claims to support fair and equal elections. I worked hard to qualify for the city’s public matching funds program; a program that’s supposed to level the playing field for grassroots candidates. I collected small-dollar donations from neighbors, documented every step, and submitted the paperwork the way I was told to. Still, the Campaign Finance Board (CFB) denied matching funds. That wasn’t just a setback. It was silencing. Without that funding, it’s harder to get my message out. Harder to print flyers. It’s harder to knock on every door. It’s harder to reach the people I’m running to represent. And the truth is, I’m not alone. Many first-time, working-class, and Black candidates. Especially those without ties to political machines, have been met with the same obstacles. We follow the rules and still get shut out. Meanwhile, candidates with insider backing seem to glide through the process. These rules are presented as neutral, but they’re not experienced in that way. In practice, they’re a barrier. And when the barriers consistently fall hardest on the same communities, we must start asking harder questions. Who Really Benefits From a “Fair” System That Isn’t Fair? Let’s be honest: when a public agency like the CFB applies its rules in ways that disproportionately disadvantage certain candidates while smoothing the way for others, that’s a form of institutional corruption. I’ve said from day one that this campaign is about real people: tenants, workers, families struggling to stay afloat. My donations come from people who can spare $10 or $25 not maxed-out checks from lobbyists or PACs. The truth is that the current system doesn’t just fail to support candidates like me; it’s designed to stop folks like us. I’m not saying envelopes are being passed under the table. But when decisions are made in ways that uphold the status quo and shut out grassroots candidates, the impact is the same: we get a system that works for the powerful and locks out the rest of us. And it doesn’t stop with the CFB. Local media doesn’t cover all the candidates, just the ones with the most money or name recognition. Community forums and debates don’t always invite everyone. Suddenly, “viability” becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: if you’re not on the invite list, you don’t get coverage. If you don’t get coverage, people assume you’re not viable. But I rejected that definition of viability. Viability shouldn’t be about who can raise the most money. It should be about who shows up. Who listens. Who understands what it’s like to struggle in this city. Who has solutions grounded in lived experience, not lobbyist talking points. I Represent This Community. Whether the System Acknowledges It or Not I’ve been in tenant meetings, school advocacy groups, and community boards long before I ever ran for office. My campaign is powered by working people like retirees, educators, parents, organizers, and hourly workers who believe in building Brooklyn where we all belong. But their voices and mine are being drowned out by a system that confuses equity with access, and democracy with dollars. State Senator Kevin Parker, who faced similar exclusion during his campaign for Comptroller, said it best: “These rules are presented as neutral, but they aren’t experienced that way.” He’s right. The system locks the door and tells us to bring our own chair but doesn’t hand over the key. We need to fix that. We need a campaign finance system that lives up to its promise of fairness. We need transparency in how matching funds decisions are made. We need media coverage that doesn’t treat underfunded candidates as invisible. And we need voters to know the full slate of choices, not just the ones who can afford consultants and mailers. I’m Still Standing Because This Isn’t Just About Me This campaign isn’t just about a seat. It’s about your voice. It’s about refusing to accept that the only people who get to govern are the ones who can afford to run. I’m not asking for special treatment. I’m asking for a fair shot. I’m asking for a system that reflects the values we say we believe in equity, opportunity, and representation. Because if democracy only works well-connected, then it’s not working at all.

By Hector Robertson, Candidate for City Council, District 35 (Brooklyn)

I’m running for New York City Council in District 35, not because I come from money, and not because I have deep-pocketed donors or political endorsements. I’m running because I’ve experienced the struggles that too many in our community face: skyrocketing rents, under-resourced schools, and a political system that too often leaves us out.

But from the moment I launched my campaign, I ran into roadblocks, not just from the usual challenges of organizing, but from the very system that claims to support fair and equal elections.

I worked hard to qualify for the city’s public matching funds program; a program that’s supposed to level the playing field for grassroots candidates. I collected small-dollar donations from neighbors, documented every step, and submitted the paperwork the way I was told to.

Still, the Campaign Finance Board (CFB) denied matching funds.

That wasn’t just a setback. It was silencing. Without that funding, it’s harder to get my message out. Harder to print flyers. It’s harder to knock on every door. It’s harder to reach the people I’m running to represent.

And the truth is, I’m not alone.

Many first-time, working-class, and Black candidates. Especially those without ties to political machines, have been met with the same obstacles. We follow the rules and still get shut out. Meanwhile, candidates with insider backing seem to glide through the process.

These rules are presented as neutral, but they’re not experienced in that way. In practice, they’re a barrier. And when the barriers consistently fall hardest on the same communities, we must start asking harder questions.

Who Really Benefits From a “Fair” System That Isn’t Fair?

Let’s be honest: when a public agency like the CFB applies its rules in ways that disproportionately disadvantage certain candidates while smoothing the way for others, that’s a form of institutional corruption.

I’ve said from day one that this campaign is about real people: tenants, workers, families struggling to stay afloat. My donations come from people who can spare $10 or $25 not maxed-out checks from lobbyists or PACs.

The truth is that the current system doesn’t just fail to support candidates like me; it’s designed to stop folks like us.

I’m not saying envelopes are being passed under the table. But when decisions are made in ways that uphold the status quo and shut out grassroots candidates, the impact is the same: we get a system that works for the powerful and locks out the rest of us.

And it doesn’t stop with the CFB.

Local media doesn’t cover all the candidates, just the ones with the most money or name recognition. Community forums and debates don’t always invite everyone. Suddenly, “viability” becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: if you’re not on the invite list, you don’t get coverage. If you don’t get coverage, people assume you’re not viable.

But I rejected that definition of viability.

Viability shouldn’t be about who can raise the most money. It should be about who shows up. Who listens. Who understands what it’s like to struggle in this city. Who has solutions grounded in lived experience, not lobbyist talking points.

I Represent This Community. Whether the System Acknowledges It or Not

I’ve been in tenant meetings, school advocacy groups, and community boards long before I ever ran for office. My campaign is powered by working people like retirees, educators, parents, organizers, and hourly workers who believe in building Brooklyn where we all belong.

But their voices and mine are being drowned out by a system that confuses equity with access, and democracy with dollars.

State Senator Kevin Parker, who faced similar exclusion during his campaign for Comptroller, said it best: “These rules are presented as neutral, but they aren’t experienced that way.”

He’s right. The system locks the door and tells us to bring our own chair but doesn’t hand over the key.

We need to fix that. We need a campaign finance system that lives up to its promise of fairness. We need transparency in how matching funds decisions are made. We need media coverage that doesn’t treat underfunded candidates as invisible. And we need voters to know the full slate of choices, not just the ones who can afford consultants and mailers.

I’m Still Standing Because This Isn’t Just About Me

This campaign isn’t just about a seat. It’s about your voice. It’s about refusing to accept that the only people who get to govern are the ones who can afford to run.

I’m not asking for special treatment. I’m asking for a fair shot. I’m asking for a system that reflects the values we say we believe in equity, opportunity, and representation.

Because if democracy only works well-connected, then it’s not working at all.