Ugly For The Empire: Why Our Beauty Won’t Free Us

A few weeks ago, Trump addressed reporters in the Oval Office about the possibility of deploying the National Guard to Chicago to threaten and harass civilians. His political leverage? The […] The post Ugly For The Empire: Why Our Beauty Won’t Free Us appeared first on Essence.

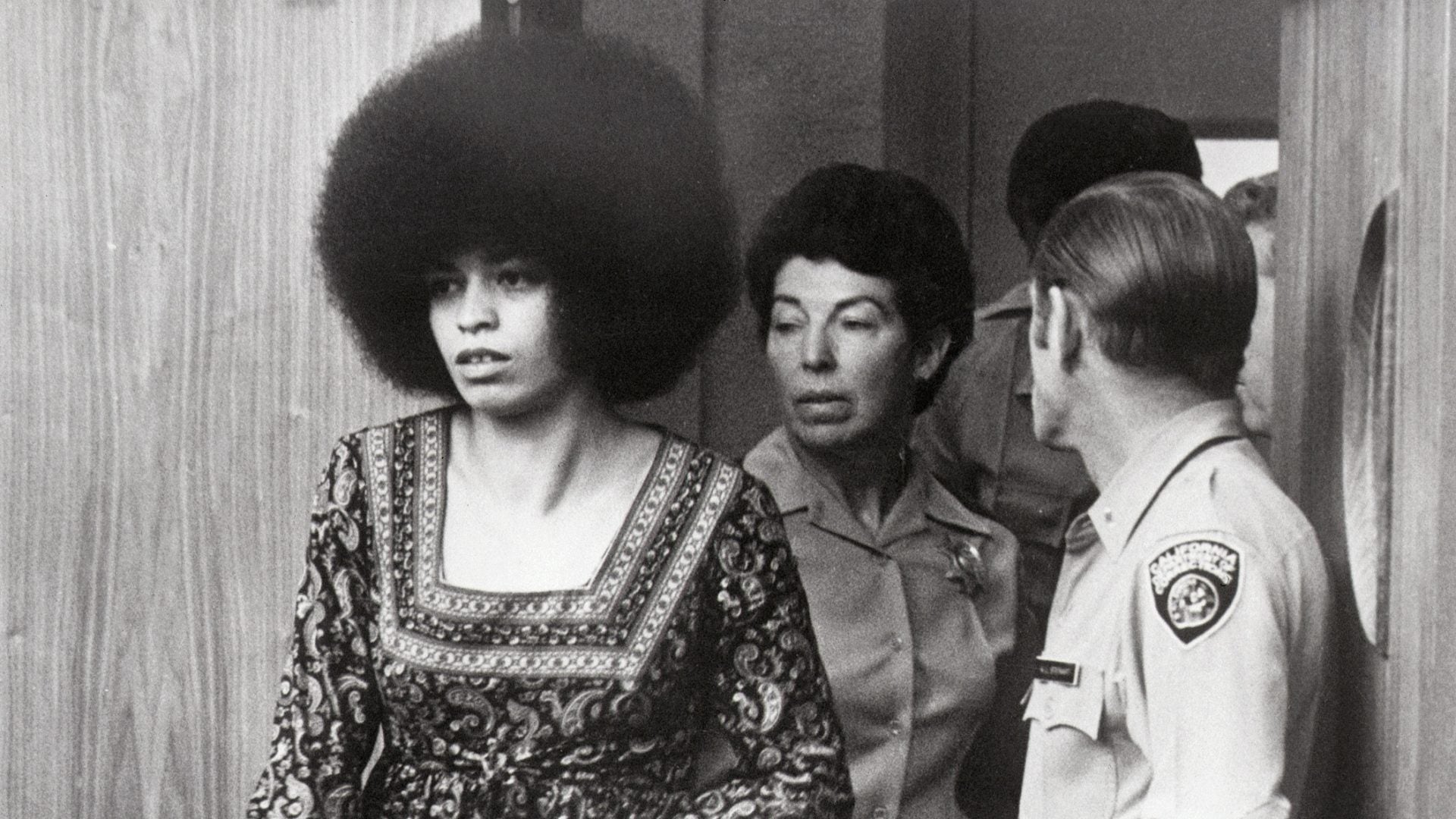

Bettmann / Getty Images

Bettmann / Getty Images A few weeks ago, Trump addressed reporters in the Oval Office about the possibility of deploying the National Guard to Chicago to threaten and harass civilians. His political leverage? The beauty of Black women. “African-American ladies [in Chicago], beautiful ladies,” he lied, “are saying, ‘Please President Trump, come to Chicago, please.’”

I know I am a beautiful Black woman from the South Side of Chicago. But when it comes from Trump—when he mentions our bodies in vanity politics for deeply violent colonial rewards—I suddenly denounce being beautiful. I want to be bladed and bulletproof.

Almost a year beyond the election of his second term, the veil has been lifted on Donald Trump’s obsession with the appearance of Black women for political gain. This new era of his empire continues his misogynoir through surveilling and fetishizing Black women, weaponizing our beauty for his own political gain. Because today’s world harbors high stakes for carrying on the tradition of beauty politics and its violence, Black women are beginning to unpack how our bodies and aesthetic tropes become battlegrounds in the American political sphere.Our beauty on political battlegrounds may seem harmless at best, tactical at worst. But make no mistake; it is never flattery. Politicians like Trump bank on the impressionability of Black women who allow him to publicly degrade us for his own power. Many see it as a continuation of Trump’s staple debasement of women, but the trend of these women’s Blackness is often left out of critiques, though it matters deeply.

During a farcical “peace signing ceremony” between the DRC and Rwanda a few months ago, Trump commented on an Angolan reporter’s looks (after being advised not to by his own press secretary). Once she spoke of the president of The Congo nominating him for an inappropriate, unearned Nobel Peace Prize, he interrupted by awkwardly inserting how “beautiful” she was, acknowledging it was “politically incorrect.” He called for “more reporters like her,” a remark deceptively flattering but ultimately derogatory and belittling.

Simultaneously, the very empire that praises certain Black women’s beauty is predicated on the erasure of those who don’t fit its grammar. For example, though Trump is openly obsessed with Black women, he has also made clear that his Achilles’ heel is “fat Black women” who challenge him, exposing his deep disgust, fear, and need to control our narratives.After years of an ambiguous, shady history with him, even Journalist Michael Wolff told The Daily Beast’s podcast Inside Trump’s Head that, “one of the motifs that was pervasive… was Trump’s attitude toward Black women. This had particular and special meaning: Black women were coming after him. And that shortly became, in his rendition of this, fat Black women.” His language here is telling; politicians like Trump use rhetoric that they perceive reduces, distorts, and punishes the Black femme body—even as being “fat” isn’t an insult at all.

Trump provides the clearest examples of how politicians use our aesthetics to pander to us, only to bait-and-switch our access and create violence around our existence. It feels like the real violence of this is in our own complicity to our fetishization in the political sphere. In patriarchal, white supremacist systems that regard beauty as capital, Black women’s bodies have always been deeply politicized.

Brittney Miles, sociology professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champagne, offers that, “Black beauty has always been politically contentious. Historically, beauty standards have been used to reinforce social hierarchies and maintain power structures, marginalizing people who don’t fit the societal standards. However, Black women have a rich legacy of strategically using their bodies, beauty practices and adornment to advocate for social change—a practice called ‘embodied resistance.’”

Even so, I just wonder how Audre Lorde would think of us using beauty as the “master’s tool” to dismantle this deadly “master’s house,” especially when both are invented by white supremacy. If you need a clearer picture of how the empire centers beauty as a construct around itself, think of Trump centering the women in his life as the “MAGA aesthetic” symbol of womanhood, and evaluating everyone against that delusional standard.Think of Kamala Harris, for example; Many have written about Trump regarding his 2024 political opponent as a “beautiful woman” in an interview with his bumbling frenemy Elon Musk, publicly connecting her aesthetically to his wife, Melania. In the same interview, he called Harris “incompetent.”When collective desires for liberation are overtaking our political landscape while creating rhetoric around our very bodies to do it, beauty feels almost archaic as a desire. I often reference Toni Morrison’s critique of the “Black is Beautiful” movement, emphasizing how obvious and pointless that argument is to make in a time when the global majority is being forced to make compelling arguments for our very lives.

The grief here is when we fetishize about ourselves what they fetishize about us. The more we care about how “beautiful” we are, even as we set beauty to new, more “diverse, equitable, and inclusive” standards, the more the empire deems that our beauty of any standard is of social value.

No, we should not constantly consider the colonial gaze when engaging with our own aesthetics, but we must unpack why our aesthetics are important to us in this time—where our desire to be beautiful comes from—and when it is platformed, especially within the same frame of beauty that colonial powers have instilled in us. The colonial world sees our beauty as a manipulative currency. And those who substitute liberation and resistance with beauty will let them, as long as it remains of value.

This dilemma isn’t about Trump; it is about us and our own self-possession. May we sublimate their gaze into resistance by continuing to show up in the world wilder than beauty can hold. May we create a visible, collective presence, with sovereignty, eroticism, self-regard, and political clarity—that empire and its cowardly stewards may never be able to name, contain, or reframe.

TOPICS: black beauty black women in politicsThe post Ugly For The Empire: Why Our Beauty Won’t Free Us appeared first on Essence.